| Intro | Bibliography | Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | ||

| Chapter 6 | Chapter 7 | Chapter 8 | Chapter 9 | Chapter 10 | Appendix | Glossary |

The overwhelming impact of Jesus and his message on the Western world has been unprecedented. It is quite unique and cannot be underestimated. The ethical system which has flowed from his teaching, and the impact of his words on everyday lives, are extraordinary. The celebration meals, by means of which Jesus announced the coming of the Kingdom of God in the lives of ordinary people, caused great offence to the religious people of the day. It was in these meals that people became followers of Jesus himself rather than members of the current Jewish religious system involving priests, Temple and sacrifice. This was his offence in the minds of the religious authorities, but his re-definition of the Kingdom of God was the means by which Jehovah, the God of Israel, was indeed to become the God of the whole world.

John Robinson has traced the history of the saying “dog in the manger” which we use in English as a negative statement about someone who is a barrier to progress. In the recently discovered “Gospel of Thomas” in Egypt, hidden amongst a lot of the Gnostic (see Glossary)teachings, the phrase appears as an original saying of Jesus, otherwise unknown. He describes the Pharisees as having a “dog in the manger” attitude. A manger is a comfortable place for a dog to lie in. The dog doesn't want to eat the hay himself, but will defend his position, preventing other animals from eating it. Jesus is saying “the Pharisees don't want what God has to offer them, and their attitude prevents others from receiving it”.

How did this saying come into common usage in the English language? Its use by people in the Middle East and Egypt down the ages may have made it known to the Crusaders, who may possibly have brought it back to England... so we have a fairly well-known saying coming down to us from Jesus himself. The things he said, and the way he taught, were so memorable that they continued in use long after their original meaning was lost.

John Robinson in his book “Twelve Studies in the New Testament”40looks at the names and family connections of the early Galilean disciples and thinks he can trace clan or family relationships between some of them. It is probable that from quite an early age, growing up with other young men and women in Nazareth, Jesus was already having a considerable impact on those around him. They may well have recognised his baptism by John as a very important turning point for him, and were evidently only too ready to respond to his call to be members of his team. The Gospels agree that fishermen “straightway left their nets to follow him” when invited to do so and the odd tax collector got up from his table without hesitation and left his work behind(Mark 1:16-20, Mark 2:14).

As long ago as 1883, Alfred Edersheim41 found that the original Apostles were actually a small group of friends and relations from Galilee, and that Judas Iscariot was in fact the only Judean among the original twelve: this may indicate that he was always something of an outsider. It was clear to Edersheim that those who received specific calls in the synoptic tradition were only the twelve Apostles, who were called in particular groups: Peter and Andrew, James and John, Philip and Bartholomew (who is thought to have been the same person as Nathaniel) and Matthew, the Publican. However, each of the others had something significant about them: Thomas Didymus (which means “twin”) is closely connected with Matthew, both in Matthew's and Luke's Gospels, where James is expressly named as son of Alpheus, or Clopas. This was also the name of Matthew Levi's father – but as the name was such a common one, no inference can be drawn from it. It seems unlikely that the father of Matthew was also the father of James, Judas and Simon, for these appear to have been brothers. Judas (not Iscariot) is designated as Lebbaeus in Matthew's Gospel, which comes from “Leb” which means “Heart”, and is also named Thaddeus, from the Jewish name Thodah, meaning “Praise”. The use of the names Lebbaeus and Thaddeus might point to the character of this Apostle as particularly hearty! Luke simply describes Judas as brother of James. We also have Simon Zelotes, which seems to indicate his original connection to the Galilean Zealot party. The historian Hegesippus, quoted in Eusebius in the 3rd Century, described him as the son of Clopas, brother of James and of Judas Lebbaeus. Hegesippus describes Clopas as the brother of Joseph, which would make these three Apostles cousins of Christ. The sons of Zebedee were his cousins also, their mother Salome being the sister of Mary.

The German Jewish textual scholar, Joachim Jeremias42 has done a lot of work to recover the original Aramaic language used by Jesus and his disciples. John's Gospel carefully preserves the actual Aramaic words used by Jesus at various crucial points in his ministry. There would be no doubt what it was that Jesus actually said. However, there may be some confusion today about what he actually meant. For instance, in the case of John 2, (see Chapter 5 of this book) Jesus uses an idiomatic expression which would only have been understood in that society at that time – much as our youngsters might use “cool” or “wicked” today. Galileans spoke with a Northern accent which was very noticeable in Jerusalem – for example, they would cut the last letter off most words when speaking: Jesus' name in Aramaic was Yeshua, which in Galilee would have been pronounced Yeshu'. North Country accents are pretty easily identifiable to Southerners in the United Kingdom as well. This is why, on Good Friday the serving girl recognised Peter as one of Jesus' Galilean followers. (Mark 14: 66-72 and John 18:15-18)

Because the former Greek Empire had been conquered by Rome, the underlying culture was Greek rather than Roman, and the common language was not Latin as one might expect. Years before the birth of Christ, the Hebrew Scriptures had therefore been translated into Greek. This collection of Scriptures in Greek was known as the Septuagint, which means “The Seventy”, due to its translation by seventy eminent Jewish scholars. It was in universal use in Israel and throughout the Diaspora (see Glossary)in the synagogues. This was to become the “Old Testament” of mediaeval Europe when it was translated into Latin, by Jerome, early in the 3rd Century AD, working in a small stone cell in Bethlehem, which can be visited today.

The Jews of the Diaspora would not all have been able to read, speak, or even understand Hebrew. They were living in far-flung, remote communities in foreign countries with a local language to master. The Pentecost story in Acts 2 shows clearly that they were not all able to speak to each other, so it was natural for the Gospels to be written in a language that most people could understand – Greek. There is a similar situation in parts of Africa where I have worked, where the national language, the language of their Parliament, is English. The individual tribes have their own languages and are not able to communicate easily with each other, even though they are part of the population of a single country... so when I preach in English in an African church or cathedral, there may be two or three interpreters translating for the different groups represented there. I have to wait my turn while they continue what they have to say – then I have to wait for the congregation to clap, and say “Amen! YES!” with their hands thrown up in the air – it takes quite a long time to get through a 15 minute sermon – but tremendous enthusiasm is generated and everybody has a great time joining in. It must have been a lot like that when the Apostles were presenting their message in distant lands.

The names of Peter, Andrew, James and John are famous as being the first to respond to Jesus' imperious call to drop what they were doing and join him, to become “fishers of men”. Some, like Martha and Mary, and probably Lazarus, Jesus was content to leave at their home in Bethany, where we know they provided for him as he passed through. Bethany was situated on the main road from Jericho to Jerusalem, and overlooked the Temple area from a distance of less than a mile or so. It was a natural stopping place before going into Jerusalem – we know from John's Gospel that Jesus visited Jerusalem on a number of occasions for festivals at different times of year. He found Matthew sitting at a toll booth in Capernaum as this was the border between one Roman province and another. (Travellers had to pay a toll when entering another province).

We know that the initial group grew to twelve and became the senior disciples who were with Jesus for almost the whole period of his ministry, and their number grew still more as he commanded others to join him on the road. The initial preaching group of twelve, sent out in pairs to preach his message in the villages, were joined by a further 72 (Luke 9–10). This meant that Jesus' ministry could impact 42 villages simultaneously. Disciples were people trained to do what Jesus did, that is to preach the Gospel and to heal the sick. They felt great excitement when they found that they were actually able to do this, and the joy of their return to share the reports of the wonderful things that God had done, encouraged the whole group. Being involved with Jesus and his ministry over the two and a half to three year period of their training, produced the very large body of reminiscences and reports that ultimately became known to scholars as “the oral tradition”.

The legacy of this huge volume of material (referred to in John 21:25) diminished with the fading memories of succeeding generations over the next 300-400 years and what we are left with today in the Gospels – while accurate and reliable reporting of what eye witnesses saw – consists of only a tiny part of the material originally available. Over the last 200 years, European archaeologists working in the Middle East recovered large numbers of scrolls which were transported to Paris, Berlin, and to the British Museum in London. Here a lot of this material still remains to be translated. Somewhere in this mass of writing one day we may hope to find a complete copy of Papias' earliest “History of the Christian Church”. Perhaps this will provide a lot more detail about the period after AD 70 when the Church faced its greatest challenges, as the Gospel was preached by small numbers of believers in the great cities of the ancient world.

Letters written by Christians to one another in the 2nd and 3rd Centuries during times of persecution and a few reports written by Roman governors such as Pliny, give a very incomplete picture of what was happening to the Church worldwide at the time. Interestingly, Pliny told the Emperor that “those foolish Christians” stayed in one of his cities during the plague to take care of the sick and provide comfort for the dying, when all sensible citizens had left. He said many of those Christians also caught the disease and died (Stevenson: “A New Eusebius”, S.P.C.K.).

It was around AD 320 that the widely persecuted groups of believers around the world found their faith to be the official religion of the Roman Empire with the accession of Constantine as Emperor. No longer did Christianity find itself in conflict with emperors who regarded themselves as gods, which had automatically made Christians outlaws, as they would worship none but Jehovah. As the State Church, membership became the main issue for political reasons, rather than salvation by grace. Church membership came to define good citizenship, as it still does in Greece today, rather than faith in Jesus as Lord. Great religious centres were established, and many of these are beautifully described by H. V. Morton, who wrote such books as “Travelling Through Bible Lands” in 1938 (Methuen). These great religious centres throughout the Middle East, Egypt and North Africa, attracted pilgrims from far and wide. These centres sought to add to their credibility through the acquisition and veneration of “the bones of the saints” and other relics, pilgrims being encouraged to venerate these as much as to worship the Lord.

When the new Emperor Constantine recognised Christianity as the official religion of the Empire, it was most likely because the Christian Church had by then become sufficiently numerous to be politically significant. He himself was not actually baptised until on his deathbed, as his lifestyle would otherwise have been restricted in accordance with Christian ethical values.

It then became important for the Old Testament and the New Testament documents to be collected together and made available in Latin. Rome being the capital city of the Empire at that time, for political reasons it had to be seen not only as the capital but also as the world's most important Christian centre. Matthew's Gospel then had to be recognised as the most important Gospel, since Matthew 16 appeared to assert that Peter was “the rock” on which Christ would build his Church (see Chapter 9 of this book). To establish the position of the Church in Rome, Peter had to be seen to be the central figure associated with Rome. It was around this time that Peter's Gospel was re-attributed to Mark, possibly to avoid the necessity of having to reorganise the canon of the New Testament so that it preceded Matthew's Gospel.

When Christianity became the religion of the Empire, all sorts and conditions of people had to be admitted to its ranks. Church membership became the most important issue in local communities. In this way, nominalism became a major factor in the life of the Church. Justification by faith alone became much less important to the religious authorities. Control had to be exercised on dogma and systems of ordination were established to ensure central control of the system. It is from this foundation that the worldwide Christian Church has grown.

The issues of faith, so important to the little Christian communities before AD 70, were no longer paramount. The great religious centres sought to authenticate their connections with their Christian beginnings by building great basilicas such as Santa Sofia in Constantinople (Istanbul) and St. Mark's in Venice. (Santa Sofia is now a mosque). The bones of St. Peter in his tomb under the high altar in Rome were matched by the bones of the saints eagerly acquired by the authorities in charge of the new religious centres.

We read in Acts that John Mark went with Barnabas on a mission to Cyprus. In the 4th Century, a story arose that he had subsequently been martyred in Alexandria, Egypt. Bones alleged to be his were acquired by two businessmen from Venice, who sold them on to be installed under the high altar of the new cathedral church in Venice, then under construction.43 This was probably not the Mark who acted as secretary to Peter as he dictated his first Gospel. Mark was a common name at this period, as were Matthew, Simon, Peter, James and John. Around this time we hear of a Presbyter John who seems to have been confused with the writer of the Gospel and the Epistles in the New Testament, by 2nd Century writers.

For all these reasons it is extremely difficult to be clear about the subsequent history of the original Apostles.

Peter went to Babylon (1 Peter 5:13). There is no 1st Century evidence that he ever went to Rome. The strong tradition claiming his presence there may have political implications rather than historical ones. Martin Luther proved that the documents claiming Papal succession from Peter were 9th Century copies of 7th Century forgeries. However, this does not mean that Peter was not in Rome at some stage – and Streeter's argument that he was never there is somewhat negated by the 2nd and 3rd Century catacombs (see Glossary) named after him, and by the well-attested evidence that Mark was there and produced a copy of his Gospel there. We know that Mark was so closely associated with Peter in local tradition that Mark's presence is to me strong evidence that Peter probably was there at some stage, even if only for a short time.

There is a lot more evidence, in Acts and Philippians for example, that Paul was in Rome. It was not until much later that people were claiming that Peter was there. Clement of Alexandria in AD 200 mentioned that he thought Peter had been in Rome. Jerome (who died in AD 240) declared that Peter, after first being Bishop at Antioch, and after labouring in Pontus, Galatia, Asia, Cappadocia, and Bithynia, went to Rome in the second year of the Emperor Claudius (about AD 42) to oppose Simon Magus, the heretic, and was Bishop of the Church in Rome for 25 years, finally being martyred in the last year of Emperor Nero's reign, AD 67, and buried on the Vatican hill. A tomb, containing bones said to be those of Peter, is under the high altar of St. Peter's Church in Rome. This all sounds very convincing, but for the fact that Jerome had lived a dissolute life as a young man in Rome and may very well have desired to rehabilitate his reputation in the Church there. There were considerable pressures on people like Jerome to say the sort of things that the authorities back home undoubtedly wanted them to say. I am rather suspicious of his motives in providing such excellent information which would have been well received by the leaders there.

James, the Lord's brother, also remembered as James the Just, remained in Jerusalem as leader of the church, where he was greatly respected within Judaism. He was affectionately known as “old camel knees” because of the horny calluses he developed through long hours of prayer (Hegesippus, “Ante Nicene Fathers” Vol. 8, www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/hegesippus.html). James' murder in AD 62 by the Jewish authorities probably marks the final break between Christianity and Judaism, as Christians had already become known as a separate entity in Antioch at least twenty years earlier.

John is regarded as the founder of Christianity in Asia; after persecution and torture in Rome under Nero, he was banished to the island of Patmos, where he received The Apocalypse (glossary) and visions concerning the Church in Asia Minor. Tradition says he was able to return to Ephesus, where he lived to a ripe old age.

James, the brother of John, is remembered in Spain as the Apostle who brought Christianity to Zaragossa. Present day Taragona in Spain was known as Tarshish, on the coast by a large river leading into the interior in the south. Miles up the river are local traditions surrounding the establishment of 1st Century churches which claim to have been founded by Paul. We know at the end of Acts, that as no charges had been brought against Paul within the statutory two year period under Roman law, he would then have been free to leave to pursue his original vision to carry the Gospel as far as Spain. This to him in those days would have been the end of the world.

Thomas is famous for his remarkable adventures in India where he became administrator for a local king in South East India, and established what was to become known as “The Thomas Church” there. This group were rediscovered as a flourishing body by Jesuit missionaries in the 16th Century44 It is probable that their forms of worship may even now reflect the very earliest Christian traditions.

The small isolated groups of believers that the Apostles and their successors were able to establish in the 1st and 2nd Centuries remained largely isolated from one another, and far-flung, with the result that they developed somewhat divergent views about the major theological issues. For instance, teaching about the nature of the Trinity was only settled in the 5th Century by the great Church Councils. Uniformity in churchmanship and doctrine was a goal never to be fully achieved. These early years provide us with very little information other than sporadic letters written by early Christians, referring to occasions when these little communities were experiencing persecution in different parts of the Roman Empire. It seems that the letters of Paul were circulated and were referred to in an account of a trial of Christians at Lyons, France, in AD 177, as a set of scrolls contained in a small wooden box. We are not told how many of Paul's letters were in the box, or which ones they were, but the Roman Governor was told that these were the letters of Paul, “a good man” (Stephenson: “A New Eusebius”, S.P.C.K.).

The Apostles regarded the Gospel as of such colossal significance that they were prepared to risk their lives to stand up and preach the Good News in the face of virulent opposition from local pagan priests. This is quite remarkable, and a sure indication of the urgency with which they regarded the task of telling the world about Jesus and the coming of the Kingdom of God. This sense of urgency is sadly missing from most of the Christian church today, which in general appears to have little intention of making Jesus known to the lost.

One of the theories I heard at Theological College was that, as one Rabbi with disciples amongst many such rabbinical groups in Israel at the time, Jesus' group was distinguished by having been called individually by Jesus himself, to be part of his group. We were taught that to join other groups, application had to be made by the student to the Rabbi. In the main I see little evidence for this distinction.

Luke 9 deals with the call of disciples, where we see Jesus passing on his way both approaching and being approached by would-be disciples. In Luke 9:57-58, someone applies to join the group: there is some evidence here that Jesus perceives the man is joining the group to meet his own needs rather than to serve. He says “Foxes have holes, and the birds of the air have nests, but the son of man has nowhere to lie down and rest”. In other words, Jesus is saying that he has no material gain to offer those who serve.

In the local idiom, “foxes” were the politicians, the extremely wily ones who gain leadership and all the perks that go with such positions. In the ancient world, if you were a farmer, you remained relatively poor. To be rich you needed some sort of business or trade, preferably trading in exotic goods such as expensive spices from the East – but if you wanted to be seriously rich, you went into politics, collected the taxes, and creamed off a large percentage for yourself. “The birds of the air” was the expression for the Roman armies, who could arrive without warning, walk all over your land destroying your crops, requisition any of your possessions they wanted, including your donkey, which you would probably never see again, and march off. Jesus was making it clear that no one should think of following him in search of earthly power or wealth.

In Luke 9:59-60 Jesus actually invites a man to follow him, and the man says “Sir, first let me go back and bury my father...”. To us it seems rather unreasonable that Jesus says “Let the dead bury their own dead, you go and proclaim the Kingdom of God.” The point here is that the man's father had not yet died. Parents depended on their children for their long term security and in this particular case, if the man's father had not yet died, he would have considered himself still to be responsible for him – so he might not actually be available to be a disciple for some years. Jesus is saying there is no priority greater than preaching the Kingdom.In verses Luke 9: 61-62, someone agrees to follow Jesus but says he must go and take leave of his family – again, it seems unreasonable to us that Jesus does not want him even to do that. The situation then was different: “Saying goodbye to the family” in their culture involved going back to the village to get the agreement of one's parents before taking up a job opportunity.45. Today in Ankara, Turkey, a senior executive in a multi-national Company may be required by family tradition to return to his village and obtain approval from his parents to any career move. The parents may well be peasant farmers with no knowledge whatsoever of multi-national Companies! What the man is actually saying to Jesus is that he wants to see if his family will agree before he can commit himself to the group. Jesus is saying that a decision to follow him must be the person's own; anyone who relies on the approval of others is not fit for the Kingdom of God.

So – there were people who applied to join his group to meet their own needs, and people who were invited by Jesus and for one reason or another were unable to respond, because of issues Jesus regarded as unimportant. The urgent need was to present the Kingdom to communities.

Many young men and women on the edges of our front line ministry in Open Air Campaigners have been inspired over the years by the tremendous effectiveness of the work we do. We have opportunities to work in several different countries, and an apparently glamorous lifestyle working from home and involving quite a lot of foreign travel. Even the local ministry amongst young people appears very attractive, as well as the exciting stories we relate of preaching on the streets. However when they take the plunge and get involved, they find there is an enormous amount of work needed in reading and preparation; there are early morning starts, nights spent in sleeping bags on concrete floors, lack of finance, and all the other struggles which go with evangelism and mission. Those who join for their own reasons as opposed to a call from God very soon move on to less demanding work.

Disciples had a specific job to do. Luke 9 shows Jesus sending them out to preach the Kingdom of God and to heal the sick. That ministry is successful, and in Luke 10 another seventy-two are sent out to do the same. He sends them out with specific instructions; “I am sending you like lambs among wolves. Don't take a purse, or a beggar's bag, or shoes, or a staff. Don't stop to greet anyone on the road.” This has normally been understood to mean that they were to travel light. Actually, the staff, the beggar's bag and the shoes were the usual equipment of disciples of one of the Greek philosophers, and Jesus probably did not want his disciples to be identified with any other group.

They were not to spend time on the road as it was imperative that they hurried on and proclaimed the Kingdom of God in each village. That was to take total priority. By the time they had travelled the considerable distances on foot, recovered from the journey, and generally got themselves together, it would be evening, and that is when the work of presenting their message would need to be done. The customary long greeting – which still takes place today in many Middle Eastern countries – with inquiries after the health and welfare of family, business, relatives etc – could take an hour of polite conversation and was to be dispensed with. No ceremonies, no greeting, just get straight down to business!

Also they were to be totally dependent on the hospitality offered in the villages where they were sent to preach. In the evenings, as people came home from the fields, there would be places where villagers would congregate to discuss the day's events and hear stories. Visiting preachers able to teach more about their God would be welcomed. One greatly misunderstood passage here refers to the need to stay “in one house” and not go from house to house. This is to do with local culture regarding hospitality and is not a reference to personal evangelism with individuals.

Travelling around Palestine on my motorcycle in the early 1960's, I was the recipient of wonderful hospitality from Palestinians who were amongst the most the delightful people I have ever met. In many cases their poverty was entirely overcome by their generosity. At other times in Iran, wealthy people have provided a splendid welcome to this traveller: I remember in a small town in central Iran, arriving to look for a hotel, and pulling up outside what looked like a castle in the main street. I asked the uniformed guard standing outside the main entrance (carrying his World War I Lee-Enfield rifle) where the hotel was. He took me inside the castle, where I was welcomed by the young owner – the Eton educated Mayor of the town! He also happened to be the son of the local war-lord. I was provided with a room with a most comfortable bed, a splendid evening meal, and a punkah wallah (servant) to operate the hand-driven fan over my bed until I went to sleep. The Ford Cortina car I was using on that particular trip was left outside until the early hours, before being parked inside the courtyard, so that the town would know that the Mayor was doing his duty and taking his turn offering hospitality to a traveller that night.

In the morning, after a cooked breakfast, I asked whether I might reimburse the cost – and was told by my host that on no account must I ever do anything like that while staying as a guest in his country. To do so would be a profound insult to the host. It was a real blessing to have met this chap as it prevented me making such an awful mistake later down the road. Both Iranians and Iraqis were keen to befriend and assist a young traveller from the West, and I treasure their memory.

In the time of Christ, and in fact probably for thousands of years, local culture dictated that the safety of travellers was sacrosanct. This was nothing to do with Mosaic Law or any religion, it was the culture of the people of the land to provide safety and protection for travellers passing through, maybe with wife, children and all their possessions, in a state of great vulnerability. If any harm should befall them on “our” territory, this would be regarded as a total disgrace. This is an ethic that pre-dates history in the ancient world and is legendary. In each village it would be the duty of individual house-holders in rotation to offer sustenance and shelter to travellers passing through. Etiquette demanded that the traveller be satisfied with whatever food and drink the host – in his poverty, maybe – was able to offer. Not to be satisfied, and to go to the next house to ask for more food, would be demeaning to the original host and simply not to be done.

The “man of peace” referred to in the text (Luke 10:6) was the person whose duty it was to offer hospitality that night. It was quite a responsibility for very poor people. This hospitality had to be available even if the traveller's arrival occurred in the middle of the night: in Luke 11, the writer assumes the reader will understand that the neighbour knocking on the door at midnight knows that his request for bread for the traveller will be granted – the “man of peace” for that night has a duty of hospitality which he is bound to fulfil. The honour of the village is at stake. Jesus' audience would have been holding their sides with laughter at the very idea of such a request being refused – it was a huge joke! Bailey explains how the word “persistence” is associated with the idea of “being blameless” and avoiding shame – the parable makes clear that the sleeping neighbour will preserve his honour and grant the host's request and more – even so, man before God has much more reason to rest assured his requests will be granted. The preservation of honour was a virtue seen in the Eastern value system as very much appropriate to God46

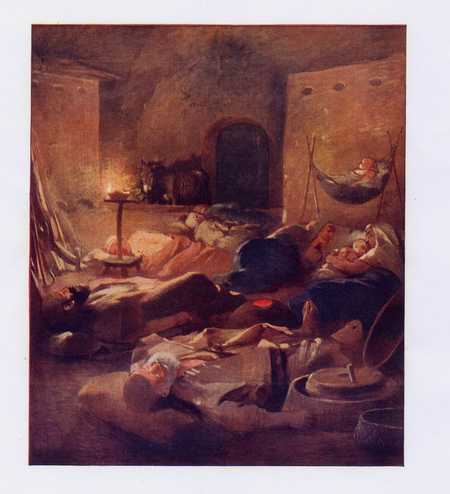

“Interior of a Fellaheen house at night”, painted by James Clark R.I. First published in 1915.

It is most important for us to understand, when talking about the need to stay “in one house”, that Jesus is instructing his disciples how to behave in a poor village. It has nothing to do with how their ministry is to be performed. They already know they are to preach the Kingdom of God and heal the sick. Misunderstanding of this passage has led to much of the unbiblical, unsatisfactory teaching of many of those who have been led astray by the modern church growth movement, who advocate personal evangelism as the only responsible way to bring people into the Kingdom. With so many people to reach in the modern world,personal evangelism is very important in dealing with long term local relationships, but as the main thrust for the Christian Church it is almost irrelevant.

We have to win the hearts and minds of tens of millions, not six more for our local fellowship. Jesus and the Apostles sought to impact as many people as possible as often as possible with the crucial message of the Kingdom of God, with extreme urgency. This is the key feature of the New Testament documents.

cf. Appendix : Patterns of evangelism in Acts – a summary of the Apostles' work.

40 Robinson, John A.T. (1984): Twelve Studies in The New Testament. London: S.C.M. Press. p. 106

41 Edersheim, Alfred: The Life & Times of Jesus the Messiah. London: Longmans Green. pp 521-522

42 Jeremias, Joachim (1971): New Testament Theology Vol. 1. London: S.C.M. Press. Chapter 1

43 Morton, Henry Vollam (1938): Travelling Through Bible Lands. London: Methuen

44 Tucker, Ruth A. (1983): From Jerusalem to Irian Jaya. Grand Rapids. Zondervan

45 Bailey, Kenneth. E. (1983): Poet & Peasant. Eerdmans. p. 22

46 Bailey, Kenneth. E. (1990): Poet & Peasant. Eerdmans. p. 132-133